Discrimination in the Targeting of Predatory Lending and Concomitant Foreclosures as Predictor of Historic Levels of Wealth Loss

Photo by Me

Photo by Me

Predatory lending and foreclosures exacerbated the racial gap in homeownership and led to historic wealth loss; past research lacked the key predatory characteristic and thus underestimates harm. With advances in data science, availability of big data, and appropriate statistical and geo-spatial models, the project will quantify the unequal wealth loss from predatory lending and estimate causal impact. The dataset integrates HMDA, assessor, census, and HUD data, ZTRAX property and voting records. We address: (1) the evolution of predatory lending mortgage originations over time and across geographic areas; (2) If loans originations had kept their pre-housing bubble and foreclosure crisis trend, what would wealth distribution be in areas hardest hit? The causal inference uses Bayesian structural time series modeling to predict the counterfactual wealth gap had predatory lending not occurred. An Emergent Hot Spot Analysis will identify hot and cold spots to predict spatiotemporal trends.

Background and Research Question

By the early 2000s the United States (US) saw the highest percentages of homeownership in history (Kochhar, Fry, and Taylor 2011). But by 2017, the percentage of property owned by Black and Indigenous People of Color (BIPOC) in the US was less than it was 100 years earlier (Agyeman and Boone 2020) and any early 2000s homeownership gains made by BIPOC had been reversed. This wealth reduction was concurrent with the largest real estate bubble in US history, characterized by inflationary price increases on homes that incentivized rapid-fire origination of “high cost” mortgages that were overpriced relative to the value of the home (Goldstein 2014). But what was the role of predatory lending and the longest and by far the worst foreclosure crisis since before the American Revolution in increasing economic inequality today?

The housing bubble, starting in 2002, followed by the 2008 market crash and then the foreclosure crisis of 2010, resulted in significant economic loss to individuals and neighborhoods. According to Kochhar, Fry, and Taylor (2011), between 2005 and 2009, the median household wealth for Black, Latino and Asian households in the United States dropped by 53%, 66% and 34%, respectively, while the median wealth of white households dropped by merely 16%. As the study explained: “developments in the housing market are the principal agents of change in household wealth from 2005 to 2009” (Kochhar, Fry , and Taylor 2011 p.17) that are largely attributable to predatory lending originations and disproportionately impacted working class communities of color, BIPOC and women heads of household borrowers. Evidence suggests these practices continue to exert a negative effect on these communities today. For example, a 2019 study conducted by the Urban Institute found that the 30% gap between black and white home ownership is greater now than before 1968, when housing discrimination was legal (Young 2019).

Evidence suggests that the home ownership gap and, therefore, wealth divide, between white households and households of color has been exacerbated by predatory lending through ongoing wealth stripping of inflated monthly billing as well as high foreclosure rates. For example, among home purchase loans made in 2006, roughly one out of every two loans made to African American (50%) and Latino (46%) borrowers were high cost, compared to fewer than one out of five loans made to white borrowers (18%) (Ben, Ellen, and Madar 2019). According to Squires (2005), the systematic channeling of otherwise qualified minority borrowers into subprime mortgages carrying high costs and risks was one form of reverse redlining. At the 2006 peak of the subprime market, 27% of all loan originations were subprime, including 49% and 39% of loans to African-Americans and Latinos, respectively (Bocian, Li, Reid, and Quercia 2011).

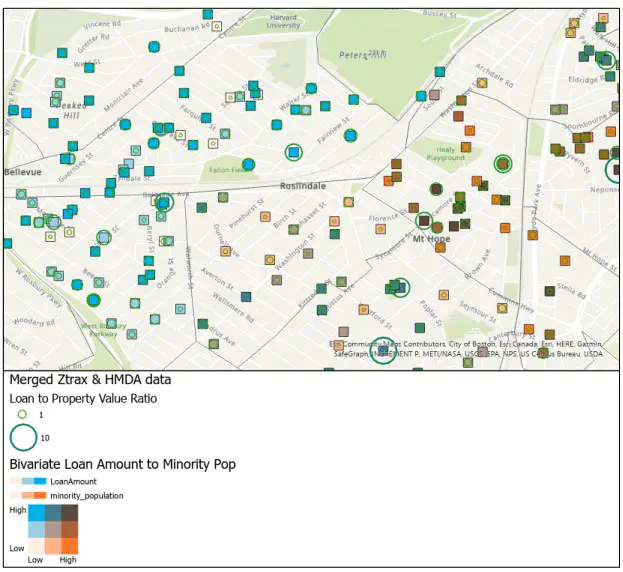

Overinflated loan-to-value ratios are the single most important factor leading to default and/or foreclosure (Quercia and Stegman 1992). Research has shown that even when loan to value ratios are raised from 90% to 97%, default rates for new homes increase seven-fold. Whereas the foreclosure crisis coincided with sharp decreases in household wealth, with and without home equity, for all families, regardless of race or ethnicity, research has shown that by 2011 wealth levels for whites began to show signs of recovery. The typical Black family, on the other hand, continued to experience severe declines, losing an estimated 40% of non-home-equity wealth throughout this time frame (Burd-Sharps & Rasch, 2015). The amount of wealth lost was and still is directly attributable to the magnitude and timing of the housing bubble in different communities: that is, predatory lending began earlier, lasted longer, and was more aggressive resulting in proportionately greater loss of wealth.

But, what would the wealth gap be had the type of lending, bubble and foreclosures never happened? Several studies have attempted to quantify wealth gap differentials across individuals and neighborhoods following the foreclosure crisis. Although these studies provide a general understanding of how predatory lending practices have targeted low-income persons of color living in distressed neighborhoods, they suffer from several methodological and data limitations. First, operational definitions of “predatory lending” have not been clearly delineated and distinguished from “subprime lending” as the latter can be legal and is not by law prohibited.

In addition, operational definitions have conflated predatory loans with practices of lenders, even though an entity deemed a “subprime lender” may originate both prime and subprime loans (Ho & Pennington-Cross, 2007). Second, different studies have weighted loan characteristics differently and, while finding measurable discrimination and negative financial consequences, previous studies have not analyzed the loan-to value-ratio , which other studies have identified as the most important factor predicting default. The most important limitation of previous research, however, pertains to the lack of applied methods to model the causal effect of the housing crisis on wealth destruction, which requires a statistical framework that predicts the course of the foreclosure crisis, and consequently wealth diminution, by examining what would have occurred had the historical levels of predatory lending origination practices never occurred.